There was nothing left of the guy, nothing at all – except a bone, a rag, a hank of hair. The guy had been trying to tell me something … but what?

– The Band Wagon (1953)

Willa: A few months ago I was joined by Nina Fonoroff, who is both a professor of cinematic arts and an independent filmmaker. We did a post about the first section of Billie Jean, and also talked about how Michael Jackson drew inspiration from the Fred Astaire movie The Band Wagon, and from film noir more generally. Then a few weeks later Nina joined me for a second post about the middle section of Billie Jean, and Nina suggested fascinating visual connections to The Wizard of Oz and The Wiz. Today we are continuing this discussion by looking at the concluding scenes of Billie Jean and some potential visual allusions in that section of the film.

Thank you so much for joining me, Nina!

Nina: Thank you, Willa! I’m hoping we’ll find a new wrinkle in the “case” of Billie Jean (the film).

Willa: Oh, I always discover something new whenever I talk with you!

So last time we looked at Michael Jackson’s iconic dance sequence in the middle of Billie Jean, with the bleak ribbon of road stretching behind him to the foreboding “Mauve City” in the background. As you described so well, it’s like the antithesis of the shining “Emerald City” we see glistening at the end Yellow Brick Road in The Wizard of Oz and The Wiz, which of course featured Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. I’m still very intrigued by that, and by your discussion of how those visual landscapes function within each film.

So that’s where we left off last time. The “Mauve City” dance sequence begins at about the 1:50 minute mark and extends to about 3:25, but about 2:45 minutes in we begin to transition into the final section of the film. First we cut to a view of Billie Jean’s bedroom – the first time we’ve seen it – and that’s followed by a series of snapshot-type images of her room. They’re kind of awkwardly framed, and almost look like  something a paparazzo or intruder might take.

something a paparazzo or intruder might take.

And then we immediately jump to the detective out on the street picking up a tiger-print rag. It’s the same rag Michael Jackson’s character pulled from his pocket in the opening scenes and used to wipe his shoe. And as we’ve talked about before, this is another connection to The Band Wagon, right?

Nina: Yes, it looks like a direct homage to the musical The Band Wagon, and specifically to a song-and-dance number within it, the “Girl Hunt Ballet,” which we’ve mentioned before. In this play-within-the-movie, Fred Astaire, who plays a character named Tony Hunter in the larger movie, and who stars in this sequence, begins his narration:

Nina: Yes, it looks like a direct homage to the musical The Band Wagon, and specifically to a song-and-dance number within it, the “Girl Hunt Ballet,” which we’ve mentioned before. In this play-within-the-movie, Fred Astaire, who plays a character named Tony Hunter in the larger movie, and who stars in this sequence, begins his narration:

The city was asleep. The joints were closed, the rats, the hoods, and the killers were in their holes. I hate killers. My name is Rod Riley. I’m a detective. Somewhere, some guy in a furnished room was practicing his horn. It was a lonesome sound. It crawled on my spine. I’d just finished a tough case, I was ready to hit the sack….

All of the well-worn tropes of the noir genre are present here: in the images, the sounds, the music, the feelings Astaire’s character mentions (lonesomeness, having personal vendettas – “I hate killers”) and his attitude of guarded nonchalance as he lights his cigarette. Later in the scene, another man appears in a trenchcoat and hat. We see him from a low angle as he emerges out of a thick fog and walks toward Riley. After picking a bottle up from the street and examining it, the strange man disappears, literally, in a flame and a cloud of smoke. And this is where Riley says,

There was nothing left of the guy! Nothing at all – except a bone, a rag, a hank of hair. The guy had been trying to tell me something. But what?

The detective is left with an enigma which compels him to pursue the disappearing man, while also falling prey to the femme fatale (played by Cyd Charisse), who doubles as a hapless victim whom Riley wants to protect until she betrays him. The whole “Girl Hunt Ballet” is an affectionate parody of the film noir genre at its apogee in the 1950s.

And in Billie Jean, too, we find many of the same elements: enigmatic characters, mysteries, clues, pursuits, deceptions, and reversals. These are deeply, if subtly, present in the story, the lyrics, the sounds, and the varied images of the short film as a whole – and many of our own responses, as we watch and listen to it.

First, there are a few different pursuits going on in Billie Jean. There’s the detective’s pursuit of his elusive prey, a disappearing man, Michael – though Michael is clearly no “killer.”

Then, Michael is the narrator of the story as well as the star of the show. Through his demeanor, his lyrics, and the whole story and setting of Billie Jean (song and film), Michael is an enigma to himself. He must consider why he has done the things he has done, that have caused him such remorse. One of his aims may be to attain self-knowledge – which I believe is what the song is ultimately about.

Finally, there’s our own perplexity, as we sort out the scattered clues that Michael Jackson himself – as our object of pursuit, our enigma, and our hero – has left behind. Aren’t we continually “going after” this man in our search for what he was “trying to tell us”? As fans, we have ourselves become detectives.

Willa: That’s an interesting way of looking at this, Nina. And those layers of mystery seem to telescope within one another. What I mean is, the private detective – if that’s what he is – really doesn’t seem that interested in what happened or whether the main character is guilty or not. He just wants to catch him on film in a compromising position. That’s his job and he’s trying to do it.

Then we as an audience are a little closer in. We do care about the main character and we do want to know what happened and why, so we’re trying to piece together “the scattered clues,” as you say. We have “become detectives” as we try to construct a narrative that makes sense.

And then there’s the main character himself, who’s even closer in – so much so that in some ways the story of Billie Jean all seems to be playing out inside his own head. It’s like he’s obsessively retelling the story over and over again in his mind, as people tend to do after a traumatic event. I mean, how many times does he repeat the line “Billie Jean is not my lover” or “The kid is not my son”? It’s almost like he’s trying to convince himself that he isn’t culpable somehow. Even if he isn’t legally obligated to provide for her baby, there seems to be an emotional connection to the child whose “eyes looked like mine,” and he seems to be working through that as he replays the story of Billie Jean over and over again.

Nina: That’s a great point, Willa. There’s a persistent disavowal of his relationship with this particular woman and child through the chorus, which carries the song’s main theme.

In the last part of the film, we hear the instrumental break with its punchy guitar riff, as the film cuts to another space. We are no longer beside the huge billboard on the ribbon of sidewalk. Between two dilapidated brick buildings, we are with Michael in an enclosed stairwell that has a somewhat claustrophobic feel.

Willa: Which seems to be a fairly accurate reflection of his psychological state at that point.

Nina: I think so, Willa. Through the lyrics especially, he has already given us a good idea of how he was entrapped or enclosed – with seemingly no way out – by “schemes and plans” that are not of his own making.

A window prominently shows us a neighbor – a woman sitting at a table right next to the window of the adjoining building, with a red phone before her. We see several quick inserted shots, where Michael spins in this small space. His “heeeeess,” which periodically interrupt the guitar riff, are precisely timed to each of his spins.

Willa: Oh, you’re right! I hadn’t noticed that before.

Nina: I don’t know whether it was planned in advance or created in the editing process, but that kind of synchronous moment recalls the one earlier in the film, when Michael’s footfalls on the lit-up squares were timed to the rhythm of the song. It’s a powerful editing device.

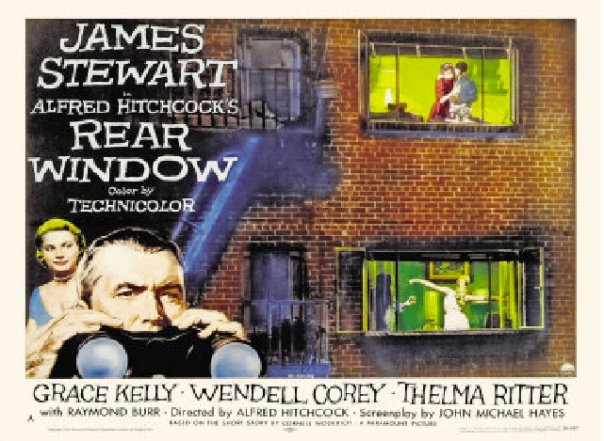

And the image of the woman in the window, as seen from outside, distinctly reminds me of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1955 film, Rear Window. Here are a couple of movie posters:

In Rear Window, L. B. “Jeff” Jeffries (James Stewart) is a professional news photographer who’s temporarily disabled; he’s in a wheelchair with a broken leg, an injury he sustained on his last assignment. Since he has too much time on his hands and is more or less in an immobilized condition, he cuts his boredom and entertains himself by spying on his neighbors, whose activities across the courtyard he can readily view through his apartment’s big picture window – which functions, for him, as a kind of movie screen. Here’s his view of a newlywed couple:

And the courtyard at dusk:

Willa: Interesting! This image of the courtyard, especially, is very evocative of Billie Jean, isn’t it? It’s the same sort of dead-end alley where Michael Jackson’s character goes to climb the steps to Billie Jean’s room.

And here’s a screen capture of the scene you were just describing of the older woman with the red phone seen through the window – the woman who later calls the police:

That could easily be a frame from Rear Window, couldn’t it?

Nina: Yes, they both evoke a very similar atmosphere and a sense of illicit looking – even though this window is closer to us than the neighbors’ windows in Rear Window, which are clear across Jeffries’ courtyard, maybe a hundred feet away.

Willa: Yes, there’s a strong feeling of intimacy in Billie Jean, and maybe that sense of intimacy, even in public spaces, is part of what makes this seem like a psychological journey – that we are inside his mind as much as inhabiting a physical space.

Nina: Yes, Willa. To name one thing, he draws his story from memory, and how can anyone gainsay that? We must identify with him, subjectively. Because he narrates, and because we see so many lingering closeups on his face (and no one else’s), because we share his emotional life on these levels, and because, as Michael Jackson, he comes to the whole scenario with the kind of star power that “needs no introduction,” we can develop very strong bonds of identification with his character, even if this character’s life situation is in no way comparable to ours.

Willa: That’s true.

Nina: Yet Michael’s gesture to the woman on the other side of the window, with her red phone and table fan, wearing something on her head that looks something like a shower cap, gives me a moment of discomfort. It’s as if some contract regarding privacy has been breached, because our sense of decorum in a city requires that a pedestrian and a resident – on opposite sides of a window – not acknowledge each other. By gesturing this “sh ush” to a stranger in her own apartment, Michael leads us to a different kind of space where conspiracy and secrecy replaces anonymity and invisibility. He is asking her not to “give him away” or reveal his presence there. According to some established social conventions, when you live in a congested city, there ought to be an implicit agreement to maintain an illusion of privacy. When you pass by an open window on the street, for instance, you are not to look in. Even if you spot a person “parading around naked” (as the saying goes), and even if some kind of sexual encounter is taking place, you are to keep walking and pretend you haven’t seen anything. (Even if they were to witness a violent crime taking place in an apartment, many people prefer just to keep their noses clean and walk past as if nothing had happened.)

ush” to a stranger in her own apartment, Michael leads us to a different kind of space where conspiracy and secrecy replaces anonymity and invisibility. He is asking her not to “give him away” or reveal his presence there. According to some established social conventions, when you live in a congested city, there ought to be an implicit agreement to maintain an illusion of privacy. When you pass by an open window on the street, for instance, you are not to look in. Even if you spot a person “parading around naked” (as the saying goes), and even if some kind of sexual encounter is taking place, you are to keep walking and pretend you haven’t seen anything. (Even if they were to witness a violent crime taking place in an apartment, many people prefer just to keep their noses clean and walk past as if nothing had happened.)

But many breaches of personal space and privacy occur all the time, beyond anyone’s control. You may sense at times that you’re living in a fishbowl where constant surveillance is your daily lot, while at the same time you are chafing under the anonymity that city life often imposes, which can provide a kind of shelter from constant monitoring but at the same time denies you the fame and notoriety you may desperately want! Those contradictions, I think, formed a large part of Michael Jackson’s life. And both Billie Jean and Rear Window are largely about blurring the distinctions between the public and the private.

Willa: That’s really interesting, Nina. And it’s true that the boundary between public and private was a fraught one for Michael Jackson – one he was constantly trying to negotiate as he dealt with that odd mix of isolation and exposure brought on by celebrity. So it’s interesting to see how that boundary between public and private is breached and redrawn in both of these films.

Nina: Yes, and it’s also telling that the staging of these stories required a sealed, private environment: both films were shot on a film set (an enclosed, controlled space), and not on location.

Jeffries is housebound, and he is increasingly fascinated by the activities he sees. He can enjoy a sense of power through his ability to control other people by narrativizing them: he makes up stories and even invents nicknames for them. First with a pair of binoculars, and then the long telephoto lens of a camera he uses for his professional work, he concocts fantasies about his neighbors’ lives as he peers into their curtainless windows. He finally becomes an amateur detective himself: his prosthetic “eyes” allow him to discover a possible murder and cover-up as he stares, transfixed, at the windows across the courtyard. The following stills show us Jeffries and the apparatuses he uses:

And then “reverse” shots that disclose his point of view, such as this shot of Mr. and Mrs Thorward:

And this one of Mr. Thorwald, a potential murderer:

And this one of a neighbor he calls “Miss Lonelyhearts”:

Willa: And again, these images are evocative of Billie Jean. For example, in this last movie still, there’s the dark brick wall outside and the well-lit space inside so that, ironically, what’s inside is more visible than what’s outside – just like the apartment of the woman with the red phone in Billie Jean. We can barely make out the bushes, gutter pipe, and iron railing outside, but we can see every detail of “Miss Lonelyhearts” preparing a romantic table for two.

So in some ways, Jeffries is like us as we “narrativize” the images we see in Billie Jean and try to form them into a story. But in other ways, he’s more like the detective character. He’s a photographer and he intrudes into other people’s private lives – just like the detective in Billie Jean – without their knowing it.

Nina: Yes, that’s true, I think – Jeffries combines both kinds of obsessive looking. What he’s up to seems sleazy, and several people in his life urge him to stop his near-obsessive spying (including his girlfriend, who at one point tells him his behavior is “diseased”). As it turns out, however, he is vindicated in the end, since his spying was instrumental in uncovering a criminal act.

Willa: He’s vindicated because his “looking” allows him to bring a murderer to justice?

Nina: Well … He starts out “spying” as a distraction, to pass the time. But then he discovers something untoward happening in an apartment across the courtyard. I won’t give away too much here, but everyone should really see this film! It’s one of the classics of the “suspense thriller” genre, which Hitchcock was especially known for.

Willa: You’re really making me want to see it again, Nina. To be honest, I haven’t watched it since I was a teenager (about 40 years ago!) so a lot of the plot details are pretty fuzzy. I do remember having contradictory feelings about Jimmy Stewart’s character, and agreeing with Grace Kelly’s character about his obsessive watching.

Nina: Rear Window has been very thoroughly studied by film critics and scholars for decades now because it so perfectly illustrates how our own physical and psychological state as film spectators are akin to Jeffries’, and especially when we view films on the big screen at the theater. We are more or less immobilized in our seats, as he is in his wheelchair, and we’re peering into a world that’s displayed before us, gazing at a screen that reveals people in their most private moments: moments that maybe we’re not “supposed” to be seeing. By all rights, we should be embarrassed by this “guilty pleasure,” but of course that’s the whole appeal of the film spectacle. Why would we give up a position where we have the distinct privilege of seeing everything that’s going on through an omniscient camera? We never get that chance in real life!

And so, it can be said that we become voyeurs every time we see a movie, just as L.B. Jeffries, watching his window as if it were a movie “screen,” is a classic voyeur in Rear Window.

Willa: Oh, interesting! And of course, that plays out at both levels in Billie Jean as well. There are the repeated scenes of voyeurism within the film, as you’ve been pointing out (the detective with his camera obviously, but also the main character himself looking at the panhandler, or looking at the woman with the red phone, or looking at Billie Jean lying in her bed) and also outside the film, as we as an audience watch the video and piece together the clues we’re given into a story.

Nina: That’s true, Willa. And yet, maybe because Billie Jean is a music video, or because it’s short (as music videos tend to be), or because it’s Michael Jackson, this main character’s mode of voyeurism seems somehow less sinister, because he’s looking at things without the intermediary of binoculars, a camera, or (usually) a window. The people he sees can see him, too.

Still, it turns out that Billie Jean’s way of telling a story and revealing information is almost as cagey as Michael Jackson himself could sometimes be! There’s allusion and implication, rather than disclosure of facts (but isn’t that’s what many works of art are about, anyway; since they’re built on metaphor)? But while most films noir assure us that we will learn the “answer” to the puzzle in due time, in Billie Jean (as in the ongoing saga of Michael Jackson’s life), while more disclosures are promised, and while we eagerly await the definitive “solution” to a riddle or mystery, the answer, of course, never arrives.

But in the end, as we watch Billie Jean – and as we regard Michael Jackson with the kind of fascination reserved for larger-than-life figures – we (or, speaking for myself here, I) am again left with a set of vexing questions about Michael himself. I’m revisiting these questions for the umpteenth time, knowing that I will never find an answer, but compelled by the process of investigation itself. Like Rod Riley and his mysterious disappearing man, I ask again and again, “the guy was trying to tell me something. But what?” I think many of us feel this way. We’re MJ sleuths.

There are many parallels, I think, between Rear Window and Billie Jean, on the thematic as well as the visual level. For one thing, there is a tradition in cinema where photography is a major motif, and photographers play a pivotal role in solving crimes … or in committing them. Here I’m thinking of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966), where a fashion photographer becomes a reluctant hero-detective; or Peeping Tom, a psychological thriller (1960) by British director Michael Powell, where an amateur-style movie camera assists a young man’s killing spree.

I’m also thinking of photography’s role in divorce cases (based on some old-school detective work) where the goings-on of “cheating” husbands and wives can be recorded as evidence. Here I’m thinking of Maurice Chevalier’s role as a Parisian detective in Love in the Afternoon, with Audrey Hepburn and Gary Cooper, from 1957, which is also the stuff of Hollywood romantic comedies from the 1930s through the 1960s. And so, what immediately came to my mind when I first started thinking about Billie Jean, was that the lyrics alone might imply a paternity suit; and a few music critics I’ve read believe that’s where things are heading in the story of Billie Jean as retold by Michael, the “narrator.”

Willa: I think so too – especially with the lines, “For forty days and forty nights / The law was on her side.” That implies there’s a lawsuit involved in her “claims that I am the one” who fathered her son. So maybe the detective has been hired to support her claims.

Nina: Yes, It would seem so, Willa; at least that’s a good possibility. It seems cryptic – but again, prescient in terms of Michael Jackson’s legal battles.

You also had an intriguing idea last time we posted, Willa, about how the man in the trenchcoat may be a detective (in the old-fashioned film noir sense), and also a more present-day kind of paparazzo. That made me think more about Michael’s many real-life encounters (pleasant and not) with photographers. And of course this bears directly on Billie Jean, as well as the first few moments of You Are Not Alone, where we see an intense display of flashbulbs going off as Michael walks slowly past a huge crowd of reporters, while singing, “Another day is gone / I’m still all alone.” An ordinary day for Michael Jackson is a day in which thousands – or tens of thousands – of photographs have been taken of him. “All in a day’s work.”

Willa: Yes. We see depictions of paparazzi in Speed Demon also, and as in Billie Jean, it ends with them getting hauled off to jail by the police. But that doesn’t mean the police are on Michael Jackson’s side – they may help him at times, but they’re a potential threat also, and so he tries to elude them as well. So there’s a constant three-way tension between him, the photographers who pursue him, and the police.

Nina: Yes, Willa, now that you mention it, his tormenters in Speed Demon are carted away by the police, while Michael goes free, thanks to his power to transform (or “disappear”) himself.

And speaking of the representation of paparazzi in more recent films, I recent came across an article by Aurore Fossard-De Almeida, “The Paparazzo on Screen: The Construction of a Contemporary Myth.” According to Fossard-De Almeida, those who practice within this relatively new profession are pure products of contemporary tabloid culture. Unlike the classic detectives of old, like Sam Spade, or Philip Marlowe, or the one-off “Rod Riley” (quasi-heroes who had smarts, integrity, and charm underneath their gruff exteriors), these guys are thoroughly despicable characters with no redeeming qualities whatsoever. They have no interest in seeing justice served.

Detectives’ work serves to uphold the law and establish “truth and justice”; therefore they have the moral high ground, even with their cold personalities and unscrupulous methods. Paparazzi’s only function in society, however, is to make a great deal of money by selling their bounty to publications whose main appeal is to the baser instincts of a public obsessed with celebrities and their downfall. Either way, this pursuer cannot be caught looking. In Billie Jean, the detective skitters around in the street, runs around corners, flattens himself against buildings. He must not be detected; and so he tries to make himself invisible, just as Michael has done, but without Michael’s superlative magical powers.

His success lies in apprehending or photographing his suspect/subject without attracting his or her notice. He should be able to watch the person while remaining out of range of any reciprocal watching: that’s his whole currency. As an amateur “sleuth,” L.B. Jeffries has to maintain his own invisibility; it’s also the key characteristic of the classic voyeur. So the detective, in his role as a paparazzo, becomes a voyeur. Michael Jackson also stands at the window of an apartment (Billie Jean’s room, we assume), looking in. He is also a voyeur, but of a less sinister kind. As the focus of our sympathy and identification (and, for many, desire), and as the object of our collective “gaze,” we might admit that “he was more like a beauty queen from a movie scene.” His distinct advantage – the ability to become invisible – is one key to his numinous beauty: in some way, we might regard him as a disembodied, pure spirit.

Willa: Which would answer in an unexpected way the central question of the song. A spirit can’t father a child since it takes a body to reproduce a body. So if it’s true that he’s disembodied, then it must also be true that “Billie Jean is not my lover.” And this interpretation is supported by the scene where he climbs into her bed and then disappears – the sheet falls flat as he dematerializes.

But he isn’t purely spirit, I don’t think. At times he seems very embodied! To me, it seems more accurate to say that he’s ever-changing – like a conjurer he can seemingly shift at will and make himself invisible or immaterial. There are also times when he’s both – when he’s invisible yet seems to have material weight – like the two scenes near the end when he isn’t visible but yet the pavers light up under his weight. So in those final scenes, he is both present and absent – material yet invisible.

Nina: Yes, I think that’s true, Willa: a conjurer is a good way to put it. And an invisible man can still have a tangible body, and even impregnate somebody: I’m sure Gothic fiction is filled with such strange occurrences!

Willa: Yes, and so is Greek and Roman mythology, and the New Testament of the Bible. I mean, that’s the miracle of the immaculate conception …

Nina: At another level, Michael’s actions in the film hint at some intangibles that, in many ways, echo his life. In Billie Jean he can “dematerialize” in order to shield himself from the prying eyes of either the law, the detective, neighbor, the photographer, but he also excelled – across his whole body of work – in making the invisible visible.

Ever since he started performing as a child, his presence as a visible force in an industry that thrives on both intense exposure (the “star system”) and secrecy, enabled him to bring some hidden practices to light. His own sacrifices to an industry that created and destroyed him served as an allegory about what happens to other children who take on the burden of too much responsibility at too young an age. The exploitation of child labor was a consistent theme of his, central to the ways he narrated his life in interviews, etc. Perhaps the ways he exposed this issue and others, was the “crime” for which he paid; some people may have feared that he was about to “blow the whistle.” But, to paraphrase Riley’s question: “blow the whistle” on what?

Willa: That’s an interesting point, Nina. He also forced us to confront some of our most intractable social problems – racism, misogyny, child abuse, war and police brutality, hunger and neglect, and other “invisible” crimes – and in doing so made them highly visible, as you say. For example, his mere presence in Dona Marta in the Brazil version of They Don’t Care about Us brought global attention and improved conditions there. As Claudia Silva of Rio’s office of tourism told Rolling Stone,

This process to make Dona Marta better started with Michael Jackson. … There are no drug dealers anymore, and there’s a massive social project. But all the attention started with Michael Jackson.

We see subtle hints of him making the invisible visible as he climbs the steps to Billie Jean’s room. Each tread lights up as he steps on it, and the letters of the vertical “HOTEL” sign illuminate one by one as he rises to their height. So his mere presence makes them highly visible.

Nina: I agree, Willa: the work he did in Brazil, for example, kind of gives new meaning to the expression, “shedding light.” And he did shed light on some realities that some highly placed people would probably rather stay covered.

Besides The Band Wagon, Billie Jean pays a more-or-less direct homage to another musical by Vincente Minnelli: An American in Paris, with Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron (1950).

I became aware of this because in September 2009, the University of California at Berkeley held a one-day conference called Michael Jackson: Critical Reflections on a Life and a Phenomenon. One presentation, by Ph.D. student Megan Pugh (“Who’s Bad?: Michael Jackson’s Movements”), pointed to a strong visual comparison between the sequence in Billie Jean where each stairstep lights up, and a musical number called “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise” that appears in An American in Paris. (The stairway sequence begins at 1:00):

The song was written by George Gershwin (who in fact wrote all the music in An American in Paris), and was first recorded by the “King of Jazz,” Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra, in 1922:

All you preachers

Who delight in panning the dancing teachers

Let me tell you there are a lot of features

Of the dance that carry you through

The gates of HeavenIt’s madness

To be always sitting around in sadness

When you could be learning the steps of gladness

You’ll be happy when you can do

Just six or sevenBegin today!

You’ll find it nice

The quickest way to paradise

When you practice

Here’s the thing to know

Simply say as you go…Chorus:

I’ll build a stairway to Paradise

With a new step every day

I’m gonna get there at any price

Stand aside, I’m on my way!

I’ve got the blues

And up above it’s so fair. Shoes

Go on and carry me there

I’ll build a stairway to Paradise

With a new step every dayAnd another verse:

Get busy

Dance with Maud the countess, or just plain Lizzy

Dance until you’re blue in the face and dizzy

When you’ve learned to dance in your sleep

You’re sure to win out

This is kind of the obverse of Michael’s simultaneous singing and dancing in Billie Jean, where he tells us how risky it can be to “dance on the floor in the round.” (“So take my strong advice / Just remember to always think twice.”)

People often frequent dance clubs when they’ve “got the blues”; they go in the hopes that dancing will help them transform their ill mood into something rosier. So much pop music, through the ages, has brought out the possibility of cheering up, of “losing your blues” through dancing. Of course, Michael Jackson himself often sang these kinds of songs as lead singer of the Jackson 5 and The Jacksons, as well as in his adult solo career. There’s “Keep on Dancing” from The Jacksons first album in 1976, with Michael singing lead:

Dancing, girl, will make you happy

And happy is what you want to be

Dancing fast, just spinning around

Dancing slow when you get down

Keep on dancing … let the music take your mind

Keep on dancing … and have a real, real good time

Keep on dancing … why don’t you get up on the floor

Keep on dancing … ’til you can’t dance no more

“Enjoy Yourself,” from the same album, is another example, with Michael singing lead:

You, sitting over there, staring into space

While people are dancing, dancing all over the place

You shouldn’t worry about things you can’t control

Come on girl, while the night is young

Why don’t we mix the place up and go! Whoooo!

By all rights, Michael’s wingtip shoes should have “carried him” away from his blues when he first met Billie Jean on the dance floor. Interestingly, the idea of dancing as a way to escape your woes, has turned to its opposite with the Thriller album in 1983, where “dancing” may result in misery. Some shift has taken place, even since 1979’s “Off the Wall” where dancing is still a harmless pastime that’s connected with achieving happiness (“Rock With You,” “Get on the Floor,” “Off the Wall,” and “Burn This Disco Out”).

What has happened, I wonder? We can blame it on the boogie, but it would seem that dancing itself can no longer be seen as a straightforward matter, and can be read as a euphemism for a sexual encounter: in this instance having unexpected, tragic results. On the album, “Billie Jean” and even “Wanna Be Startin Something” (“you’re a vegetable, they eat off you, you’re a buffet”), are the two tracks that several writers believe to have marked the initial stages of a “paranoid” tendency in Michael’s songwriting: and in their view, this tendency would become more prominent in his later albums.

And so, in Michael’s fateful encounter with Billie Jean – a girl he apparently picked up and casually bedded after meeting her for the first time at a club – dancing didn’t remove his unhappiness, but deepened it. Throughout the film, his demeanor is somewhat despondent: he sighs, frowns, and sings lyrics about how he rues the day he and Billie Jean first “danced.” Nevertheless he is about to reenact, before our eyes, the same error that initially brought him to this regrettable state, as he spins in Billie Jean’s garbage-strewn, graffiti-ridden stairwell.

Willa: Hmmm … That’s really interesting, Nina. I’m not sure that the main character “bedded” Billie Jean – I think that’s left pretty indeterminate, with contradictory clues – but it is true dancing has taken a sinister turn in “Billie Jean” that we haven’t seen before. I’m quickly running through Michael Jackson’s albums in my mind, trying to think of other songs where dancing leads to misery. There’s “Blood on the Dance Floor,” of course – but in many ways that song feels to me like a retelling of “Billie Jean,” so it makes sense they would share that connection.

Nina: Yes, that’s a good point; I also wonder if any other songwriter has written such a tale of woe about dancing.

Michael’s ascension of the back-alley staircase in this “slum” dwelling (as we might describe it) of course contrasts hugely with George Guétary’s opulent fantasy staircase, with its glamorous showgirls and ornate candelabras. Michael’s character will surely not “win out,” nor will he find any stairway to “paradise” or “heaven” (Led Zeppelin) through his dancing – only his divided self, a guilty conscience, and a compulsion to return to the sordid scene of his “downfall.” Instead of finding (or building) paradise, he seems to fear he’ll be sent in the opposite direction. But he dances and goes upstairs anyway.

As Megan Pugh observes,

Jackson zooms between a longing for the dreamworld of Hollywood Musicals – where you can solve problems by putting on a show, where boy gets girl, and where everything ties up neatly – and the realizations that such dreams may not be attainable. For in the end, Jackson almost always ends up alone.

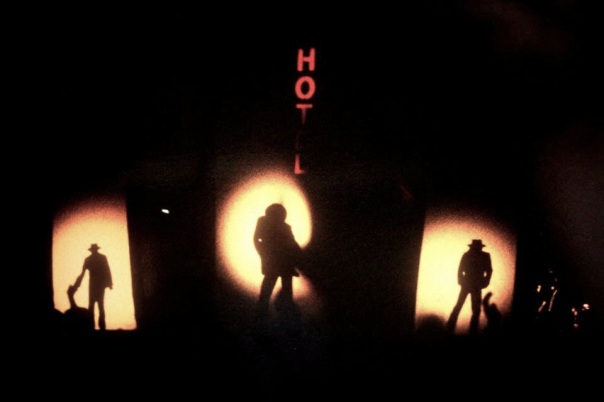

As he lights up each step, the neon sign “HOTEL” is also lit, one letter at a time. This HOTEL sign became a regular feature of Michael Jackson’s concerts, when he performed as a silhouette behind a screen that accentuated the sharpness of his moves. It was used as an introduction that preceded either “Smooth Criminal” or “Heartbreak Hotel” on the Bad tour.

Willa: Wow, that’s fascinating, Nina! Here’s a clip of “Smooth Criminal” from Wembley Stadium in 1988, and we can clearly see the neon “HOTEL” sign with the red letters arranged vertically. It’s just like in Billie Jean, but I hadn’t made that connection before.

As it says in the voiceover,

My footsteps broke the silence of the predawn hours, as I drifted down Baker Street past shop windows, barred against the perils of the night. Up ahead a neon sign emerged from the fog. The letters glowed red hot, in that way I knew so well, branding a message into my mind, a single word: “hotel.”

So he draws our attention to this “red hot” hotel sign both visually and aurally, suggesting it’s an important element for him.

Nina: Yes: and thanks, Willa! I’ve often wondered what was being said there, but I never heard the words on a good sound system. So here we have an idea of the “red hot” letters branding our protagonist’s mind – like a mental stigmata – along with certain “perils of the night,” and his musings that he knew these red letters “so well.”

By this account, then, our hero seems to be taking us on an imaginary journey to the “red light district” of the city, where his memory reveals his repeated visits to a certain house of ill-repute.

“The House of the Rising Sun,” a song that was recorded by just about everybody, was made most famous by The Animals in the 1960s. Here are some lyrics that are used in another version, recorded by a woman:

There is a house in New Orleans

They call the rising sun

It’s been the ruin of a many a poor girl

And me, oh god are one

If I had listened like mama said

I would not be here today

But being so young and foolish too

That a gambler led me astray

Again, we have a mother whose advice to her child went unheeded, as it did in Billie Jean:

And mother always told me

Be careful who you love

Be careful what you do

’Cause the lie becomes the truth

The many recorded versions of “House of the Rising Sun” reveal the song’s storied history, where the “house” is sometimes (most obviously) a bordello in New Orleans, a women’s prison, or a nightclub that serves as a gambling den, among other kinds of places. Nowhere in “Billie Jean” do we have the sense that she is a prostitute, but there are some common themes in those lyrics, such as giving in to temptation, experiencing remorse, and being “led astray” by an unscrupulous lover.

This places the story of “Billie Jean” in a folk-blues-country tradition, where there are so many songs that impart this message: you disregard your mother’s wisdom at your own peril. Another example is “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane,” of which countless versions have been recorded, many with different lyrics and in different musical styles.

Hand me down my walking cane

Hand me down my walking cane

Oh hand me down my walking cane,

I’m gonna leave on the midnight train

My sins they have overtaken me.

If I had listened to what mama said

If I had listened to what mama said

If I had listened to what Mama said

I’d be sleepin in a feather bed

My sins they have overtaken me

I’m sure there are many, many other examples.

Willa: Yes, there really are. One that immediately springs to mind is the old Merle Haggard song “Mama Tried,” with this attention-grabbing chorus:

I turned twenty-one in prison doing life without parole

No one could steer me right but Mama tried, Mama tried

Mama tried to raise me better, but her pleading I denied

That leaves only me to blame ’cause Mama tried

Nina: Oh yes, that song was in the back of my mind, but I couldn’t quite place it! Thanks for reminding me, Willa. Michael Jackson clearly absorbed and understood these songs and their themes, whether or not he consciously inscribed them into his lyrics. In some ways, we might say that he re-wrote some traditional songs in ways that could later be recognized as the timeless folk songs of a new generation. (Although it’ll be a LONG time before his compositions pass into the public domain!)

As for the vertical “HOTEL” sign, here’s one that’s beautifully photographed in black-and-white with window reflections:

This still is from the 1946 noir film, Murder, My Sweet, directed by Edward Dmytryk. Here, Dick Powell (an actor and singer who is best known for his roles, a decade earlier, in a series of depression-era musicals) – appears as hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe. It’s possible that Michael Jackson, or Steve Barron, or another person involved in the production of Billie Jean, drew from this image – which had been “branded” indelibly into their mind.

As we were saying in an earlier post, according to AMC Filmsite commentator Tim Dirks on the film noir genre, these films often featured

an oppressive atmosphere of menace, pessimism, anxiety, suspicion that anything can go wrong, dingy realism, futility, fatalism, defeat and entrapment.… The protagonists in film noir were normally driven by their past or by human weakness to repeat former mistakes.

Michael’s predicament in Billie Jean readily fits several of these elements. As we’ve discussed before, he implies that he was driven by “human weakness.”

People always told me be careful what you do

Don’t go around breaking young girls’ hearts

But she came and stood right by me

Just the smell of sweet perfume

This happened much too soon

She called me to her room

Here, his “Human Nature” is among the qualities that elicits our sympathy. This is also where “voice-over” narration – a prominent characteristic of so many noir films – becomes important in the ways we identify with the main character. The voice of the hard-boiled detective, often delivered with a studied coldness and cynicism (and parodied by Fred Astaire as Rod Riley in “Girl Hunt Ballet”), has become part of the mythological fabric of American popular culture. And this man is almost always talking about events that have occurred in the past. His portentous tone of voice signals an anxiety about even more fearsome events yet to come, including the possibility of facing danger, even death. Like our protagonist in Billie Jean, he becomes the focal point of our identification.

We identify with him, first and foremost, because his voice fills our ears, and his story fills our psyche. But the noir antihero is also someone whose distance and detachment we can almost palpably feel – not necessarily because his life or his values are so different from ours, but because we’re hearing him describe a world that exists only his head, and that he cannot share.

Willa: Interesting. And that’s precisely the feeling we were describing earlier with Billie Jean, though it’s achieved in a different way. Michael Jackson’s character is not a tough, not a “hard-boiled detective,” and he doesn’t tell us the story in a voice of “studied coldness and cynicism,” as you described.

Nina: True, and certainly by the ‘80s, these archetypes were long overdue for another update! (The image of these kinds of men had already altered somewhat in the ‘60s and ‘70s.) In the 1980s, the kind of hard-boiled masculinity that’s apparent in Humphrey Bogart, Dick Powell, and other classic movie detectives was due for a complete overhaul.

Nina: True, and certainly by the ‘80s, these archetypes were long overdue for another update! (The image of these kinds of men had already altered somewhat in the ‘60s and ‘70s.) In the 1980s, the kind of hard-boiled masculinity that’s apparent in Humphrey Bogart, Dick Powell, and other classic movie detectives was due for a complete overhaul.

New or old, though, these figures seem unapproachable on an emotional level, although at times they reveal a vulnerability that goes to the heart of their humanity. In any case, our desire to share their knowledge – to learn what they know, so that we, too, can become active participants in their criminal investigation – exerts such a strong hold on our imagination that it almost compels us to identify with them. (This goes for L.B. Jeffries in Rear Window too, though not so much for the “detective” in Billie Jean, who doesn’t know anything as far as I can tell!)

But, like Michael Jackson’s other performances, Billie Jean puts a tear, or rip, in that mythological fabric where we find the kind of masculinity that the noir detectives and action have shared, seemingly forever, in American cinema.

But, like Michael Jackson’s other performances, Billie Jean puts a tear, or rip, in that mythological fabric where we find the kind of masculinity that the noir detectives and action have shared, seemingly forever, in American cinema.

Willa: Yes, and he seemed to actively play off that 50s style masculinity – the figure of man as a stoic loner – by adopting the suit and fedora of men of that era, but displaying emotions and a sensitivity toward others that they rarely showed.

Nina: Yes, in the film this display of emotion comes through partly because he sings and dances, which are things that imply passion, vulnerability, and emotion. As writer Jonathan Lethem writes in his essay “The Fly in the Ointment,”

there’s something about a voice that’s personal, that its issuer remains profoundly stuck inside, like the particular odor of shape of their body. … Summoned through belly, hammered into final form by tongue and lips, voice is a kind of audible kiss, a blurted confession, a soul-burp. … How helplessly candid! How appalling!

I also think part of Michael’s more sensitive persona came about because 1980s pop culture generally featured less convention and more free-play with the styles of gender expression. Joe Vogel’s article in the Journal of Popular Culture, published this June (“Freaks in the Reagan Era: James Baldwin, the New Pop Cinema, and the American Ideal of Manhood”) speaks to this very phenomenon. He points out the ways Michael Jackson, along with Prince, Madonna, Boy George, David Bowie, and Grace Jones “openly experimented with and transgressed gender expectations.”

I see Michael’s suit and fedora as accouterments, theatrical props that were meant to provide a fairly self-conscious reference to these earlier (1940s-50s) film styles. At least a few of Michael’s films, from Billie Jean to Thriller to You Rock My World, were outright genre parodies. His character in Smooth Criminal was a 1987 “re-do” of Fred Astaire’s Rod Riley (from 1953), and the two film segments share the same feeling of self-conscious parody. In fact, The Band Wagon was made at the same time that some “genuine” noir films were still being turned out by the Hollywood studios. Strangely, both the parody and the “real deal” could coexist in the film world of the 1950s.

But from at least the 1980s until today, the signifiers of the noir-type film have shifted dramatically. (Recent decades have seen the rise of “neo noir” films, as Elizabeth pointed out in a comment on Part 1). Unless the more recent films are meant as a strict parody of the earlier noir style, all those trenchcoats, fedoras, two-toned wingtip shoes (or spats, as in Smooth Criminal), and voiceovers of the hard-boiled tough guy – including the ’40s slang expressions he uses – are a thing of the past, and have a kind of “camp” value when used today. Even Billie Jean, in 1983, was “camping” on those old styles. Of course, the hyper-masculine characteristics of those “hard-boiled” figures persist; but their tone has shifted, and they’ve been updated with different clothing, voices, inflections, etc.

Because the detective in Billie Jean is, for our purposes, useless as a figure of identification on any level, Michael’s character functions as both the detective and the criminal. This makes him doubly alone. It’s no accident that he’s framed by himself in almost every shot. Here, where he’s leaning against the lamppost, oblivious to the detective, is one of the only moments where the two men are framed together in the shot:

And because the detective who has taken on this “case” is an incompetent buffoon, Michael is left to investigate himself, since investigation itself is a formal requirement of the genre.

Willa: That’s a fascinating way of seeing this, Nina! – that he is, in a way, investigating himself. He does seem to be interrogating himself in the lyrics …

Nina: Yes, the vehemence with which he defends his honor, seems at some point to turn around and become a self-interrogation. And I don’t know how, in the first place, they came up with idea of the noir style for the design of this film. Someone (probably Steve Barron, or he and Michael together) had to assess the song with an eye toward what kind of scenario would be most suitable. If you decide to use all the well-known elements of a noir/detective movie, then it follows that there has to be some kind of investigation!

When he arrives at the top landing, we see Michael framed as though he were looking through a window, observing whatever he views inside the room (we presume). Then the detective who has been pursuing him appears below. He is about to follow Michael upstairs, when the woman with the red phone, still sitting in the window, places a call. We don’t yet know who she calls, or why. But now it appears that Michael can move through walls, as we see him standing inside the room he was surveying from outside, just a moment ago – the same room where, in a few flashes, we earlier saw the four-poster brass bed and the curtains hung around it.

As an aside, here’s an endearing anecdote I found by Raquel Pena, the young woman who played Billie Jean all those years ago. She is interviewed by a blogger named Marc Tyler Nobleman:

Q: How was it to work with Michael Jackson? What was he like?

A: He was fantastic! I have worked with a lot of celebrities, and he was hands down, without hesitation, the sweetest, kindest person I had ever met and worked with…… He had such a playful, kidlike spirit. There were several sets designed for the different vignettes and I remember Michael would do funny things…like he’d sort of disappear into the maze and then pop out of nowhere and “boo” whoever was walking by (he got me more than once). He was working and serious one minute and then goofing around and just having fun with everyone the next.

Last scene of the video, I had to lie down in the bed (it was actually a wooden board with a sheet over it). They wanted to give the illusion that the body in the bed was Billie Jean. I remember looking up and Michael was staring down at me, and I was like, “OMG, Michael Jackson is jumping in under the sheet with me!”

At one point during the day, Michael pulled me aside and said, “You know you’re Billie Jean, right”—more as a statement than a question. He was trying to be serious, but he had that MJ grin … he was playing with me again. I found out later that he and his brothers used to call the zillions of groupies that were always after them a “billie jean” after an incident with one crazy groupie in particular who was really named Billie Jean.

Willa: Thanks for sharing that, Nina! I love her description that “he was hands down, without hesitation, the sweetest, kindest person I had ever met” and that “He had such a playful, kidlike spirit.” I can believe that!

Nina: Yes, it’s consistent with so many other testimonials we’ve heard, about how easy it was to work with Michael.

In the classic noir films, the criminal never gets away with their crime (as per the Production Code, which we discussed in an earlier post). But in the real world, we can fairly predict how these events will unfold, at least about one aspect of the situation. The detective climbs the staircase, as we’d seen Michael do moments earlier. Presumably the two would meet at the top landing. In any American city today, if a neighbor calls the police to report a disturbance, and if that disturbance turns out to involve a black man and a white one, then it probably won’t go very well for the black man – no matter how good-looking or well-dressed he may be.

Willa: Though by the time the police arrive, Michael Jackson’s character is gone, right? He dematerializes under the sheets on Billie Jean’s bed. So when the police arrive, all they see is a man with a camera taking a picture of a woman alone in her bedroom. They never see Michael Jackson’s character.

Nina: That’s right, Willa. When Michael slips under the sheets of the bed alongside Billie Jean, who is entirely covered by the sheet, he lights up the whole bed. He is fully clothed, which is probably disappointing to some of us. (All that fuss, and he doesn’t even so much as take off his shoes!) Meanwhile, the detective stands outside the window with his camera raised to his eye, while Michael vanishes, leaving a sleeping Billie Jean under the sheet. So at this point, the detective/photographer may well be perceived as a kind of “pervert” – a prowler, exhibitionist, or pornographer. At any rate, he’s clearly up to no good.

Here, a kind of realism, based on what we know about the world today, is turned on its head. The police nab the white “detective,” not the black “suspect.” The implication is that not only has an innocent man been allowed to escape, but the detective/paparazzo, a thoroughly shady character who elicits none of our sympathy, will probably be nailed for something.

Billie Jean’s narrative produces themes of false prosecution and an innocent man accused, in ways that seem remarkably prescient in light of later developments in Michael Jackson’s life.

Willa: Yes, that’s something Veronica Bassil explores in depth in her book, Thinking Twice about Billie Jean.

Nina: Yes, and it’s strange to consider that an artist might be able to foretell the events of their future – at least the basic outlines of what may occur later in their life. It’s as though they had a nightmare, and some version of it actually came true.

But for fans, too, the film’s outcome defies social reality in a way that may make it a dream of wish-fulfillment (Michael survives and his tormentor is punished). I imagine this would be especially true for people who followed Michael’s legal battles closely in the last years of his life. As the 1990s and 2000s wore on, the legions of corrupt and opportunistic tabloid writers and photographers – who impaired Michael Jackson’s reputation and hampered his freedom in many ways – caused heartache for those fans who have wanted to hold people like Martin Bashir, Diane Dimond, Maureen Orth, and even Oprah Winfrey accountable for their unfair treatment of him.

In Billie Jean, the two cops apprehend the detective at the top of the staircase, causing him to drop his camera. They lead him down the stairs, undoubtedly over protestations of his innocence (we imagine). In this improbable scenario, Michael has narrowly escaped arrest (or worse), but only by dint of his ability to disappear.

Consistently throughout his body of work in film, Michael Jackson plays characters who pass for “normal,” yet can transform themselves to escape detection. In Thriller, Ghosts, Remember the Time, Speed Demon, and other of his short films, Michael stands in for embodied physicality: a person who is transformed into creatures made variously of papier maché, clay, metal, fur, plastic, bone, ectoplasm, dead (or maimed) flesh, and even nothing: or at least nothing that can be seen. Again, “There was nothing left of the guy! Nothing at all!”

Yet there’s also a contradiction in the star’s life, where Michael Jackson’s own hypervisibility, from the time he was a very young child, required that he invent a number of disguises. There were undoubtedly times when he wished he could disappear. There’s a tragic irony that I imagine would apply to many well-recognized stars: Michael was seen by everyone, and no one. If anything, his hypervisibility ensured that he would remain profoundly unseen.

Here are the opening paragraphs of Ralph Ellison’s classic novel, The Invisible Man (1952):

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is it though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination – indeed, everything and anything except me.

Nor is my invisibility exactly a matter of a biochemical accident to my epidermis. That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality….

Willa: I’m so glad you brought in that quote, Nina, because it really gets to the heart of this idea of invisibility in terms of race – specifically the invisibility of black men. It’s always seemed to me that Michael Jackson is referencing these lines directly in the lyrics of “They Don’t Care about Us”:

Tell me what has become of my rights

Am I invisible because you ignore me?

Your proclamation promised me free liberty

I’m tired of being the victim of shame

They’re throwing me in a class with a bad name

I can’t believe this is the land from which I came

You know I really do hate to say

The government don’t wanna see

But if Roosevelt was living

He wouldn’t let this be

Especially the lines “Am I invisible because you ignore me?” and “The government don’t want to see” seem like a direct reference to Ralph Ellison’s “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” And his invisibility is an important element in Billie Jean, Speed Demon, Remember the Time, and Ghosts, as you pointed out earlier, Nina. But in all of those instances, he uses it to his advantage, as you said, while Ellison is protesting his invisibility. The key seems to be control, being able to appear invisible or visible – even highly visible – as needed.

Nina: I agree, Willa. And thanks for these lyrics – it had slipped my mind that Michael had used the idea of invisibility here. I’m sure he would have wanted to stage his own disappearances, and to control how and when his “episodes” of invisibility would take place.

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ recently-published memoir, we read about the death of Coates’ Howard University friend, Prince Jones. In his twenties, and the son of a black woman who worked her way up from poverty in the south to become a physician, Jones was pursued across several states by the police and eventually shot by an officer – although he bore no resemblance to the man they were actually looking for.

Then very recently, this news story broke: James Blake, a retired tennis star, who was mistaken for another man. He is leaning against a structure and apparently minding his own business, when he is abruptly tackled and brought down by an assailant, a plainclothes officer with the New York Police Department.

Willa: Wow, the image of James Blake leaning against the column of the hotel is reminiscent of Michael Jackson’s character leaning against the lamppost in Billie Jean, isn’t it?

Nina: Yes, and this is another case of a striking misrecognition. The plainclothes cop was looking for someone else. It would seem that the fact of having dark skin is enough to make a person hypervisible, as well as invisible (as Ralph Ellison describes it). As I mentioned earlier, about city dwellers walking past a window and pretending not to have seen anything (even violent activity), we note here that all the passers-by are “keeping their nose clean” and minding their own business.

Also, we’re confronted with the fallibility of the photographic image when it’s used as a way of identifying a suspect. According to an article by Shaun King about the James Blake case: “Not only was tennis star James Blake innocent, so was the other black man NYPD said he looked like.” Here’s Blake’s testimony:

I was standing there doing nothing — not running, not resisting, in fact smiling,” Mr. Blake said, explaining that he thought the man might have been an old friend. Then, he said, the officer “picked me up and body slammed me and put me on the ground and told me to turn over and shut my mouth, and put the cuffs on me.

As we contemplate what happened to James Blake, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, and so many others at the hands of the police, we may recognize that the device of making oneself invisible for the purpose of sheer survival may not be such a pressing concern for those who are visibly white. Racial profiling is one direct consequence of the hypervisibility of dark-skinned people in this country; and for Michael Jackson, it was also a consequence of his extreme fame.

But for Michael, in another sense, invisibility and hypervisibility are flip sides of a coin. By being seen too much, by being ubiquitous, he was profoundly unseen. That motif of invisibility that we see across a number of his films, was perhaps his way of reflecting upon the ways prosecutors, the press, and the public are very quick to attribute wrongdoing to a person who is both widely seen, and also unseen in specific ways: that is, mistaken for another, misperceived, misrepresented, and falsely accused.

Also, Michael does a lot of looking. Throughout Billie Jean, we observe his calm, steady gaze, and we look at him looking at things.

Willa: That’s true. Except for the scenes where he’s dancing, he seems pretty contemplative throughout Billie Jean – and often he’s contemplating something that gives an indication of what he’s thinking.

Nina: If not the very content of his thoughts, then at least a sense that he’s lost in thought. Once we glean what the song is about, though, it all fits together: he’s preoccupied with this problem he’s telling us he has to face.

A few months ago, you and Joe Vogel were discussing D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film, Birth of a Nation. In that film we see very few closeups of the black characters (actually played by white actors in blackface). A closeup is one device that film (as opposed to live theater) affords us: a glimpse into the character’s state of mind. Even in a more distant shot we can sometimes see the actors’ expression and the direction of their gaze. Often the closeup will be followed by a “reverse shot” – the character is looking at something, and the film quickly edits to what he or she is looking at. In Billie Jean, this occurs when Michael first sees the homeless man who was partly hidden behind a garbage can, and also when he is wiping his shoe.

This is a very powerful cinematic device, and it’s so common that we probably take it for granted most of the time; yet it’s what glues us to the character’s point of view. Following from this, we develop a strong bond of identification with any character whose eyes we see through, whose voice we hear, whose inner life we can discern, through the film’s images and its sound – including dialogue, narration, or something else we can associate with that character.

Willa: That’s really interesting, Nina. It’s true that seeing something through the eyes of another person is a powerful way of creating a feeling of intimacy and identification. In fact, it’s the very basis of empathy.

Nina: Yes, exactly, Willa. Billie Jean establishes Michael’s eyes: closeups of his face, shots of him looking around him as he strolls down the street. We know his moods. He can be agitated (when singing and dancing), reflective and absorbed (when walking), and perhaps sad (when standing, and not singing). The agitation we feel through him, when he’s singing and dancing on the ribbon of sidewalk, is of course a function of his remarkable skill at physically interpreting any song through his voice and body, with just enough exaggeration; that’s the power of his performance style.

Following from your conversation with Joe, then, we can see that almost from the beginning of mainstream American cinema, we have rarely been afforded the chance to perceive the world through the eyes and ears of a nonwhite character, taking on their point of view. And at the time Billie Jean was made, early in 1983, there really would have been no major roles for someone like Michael, much as he aspired to branch out into film acting.

Since most Hollywood films (then and now) are made for white audiences, it may not surprise us to consider that white characters’ interiority – that is, their subjective point of view – will be prominent in the way the story is told. Black, Latino, Native, and Asian characters will assume their places as pure spectacle; only recently has this started changing. (The representation of women, of any race, has of course been discussed by feminist and other film scholars for decades now: it’s a huge issue, best left for another time.) In any case, in Billie Jean, we’re privy to a whole range of the character’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, and memories – all of which are yoked to a black body. In some ways, it’s more personal than either Thriller or Beat It. Not until the Bad film do we have another such character study.

Willa: Though Beat It does have quite a few shots that seem to reveal the main character’s “interiority,” as you say – especially in the first half of the film. In fact, there’s one shot at the end of the pool hall sequence where we’re drawn so close to his face that his breath practically fogs up the camera lens …

Nina: True, but as I see it, he’s singing at that moment – not brooding, and not looking around. The essential thing about the closeup as a glimpse of a character’s interior state is that we see his gaze, and also what it is he’s looking at. That is, we should see his point of view. The face expresses the mood, but we must also look at the world through his eyes.

Willa: Oh, I see what you’re saying.

Nina: If he’s right in our face it’s more a self-conscious moment, as if he is breaking the “fourth wall” so to speak, by directly addressing the camera, and therefore, us. In this and other ways, Michael in Beat It is positioned as a “natural” part of a group. Although “different from other guys,” he’s a social creature in Beat It, while in Billie Jean he comes across as somewhat antisocial: an inveterate loner. In the end of Beat It, he even dances with the group; while in Billie Jean, he dances strictly alone.

Upon leaving Billie Jean’s room he’s invisible. We see his traces, however, as the pavement lights up under his feet on the sidewalk where he first appeared. The billboard reappears to the right of the sidewalk, this time with an image of the brass bed where Michael lately was – the display may be a haunting reminder of the memory that he wishes he could forget.

Willa: Nina! In all the hundreds of times that I’ve watched Billie Jean, I’ve never noticed that before! My eyes were always drawn to the rapidly moving trail of lighted tiles on the left side of the screen. But you’re right, at about 4:27 the billboard appears on the right side of the screen, and it’s now showing a view of Billie Jean’s bed. Here’s a screen capture:

Wow! Very interesting. So that reinforces the interpretation from our first post that the billboard seems to illuminate his thoughts or memories of Billie Jean.

Nina: True: it implies that wherever he goes, he may be haunted by this recurring image – it can spring up in front of him at any time. Our traumas are projected on a public surface for all the world to see. What a nightmare.

In the last few moments of the film, we see the two cops leading their “nabbed” detective down the street, and the formerly homeless man crosses their path, arm in arm with a woman (a date, we assume). Meanwhile, the uncanny presence of the “invisible man” is felt as successive tiles light up, marking his progress down the sidewalk. The tiger-print rag has reappeared on the sidewalk, and the large yellow cat enters the frame and appears to take it away, as the tiles continue to show Michael’s invisible (but perhaps felt) presence. The song and the image fade out.

Willa: Hmmm … that’s interesting, Nina. I’ve always interpreted that final scene a little differently – that the detective drops the tiger-print rag and then, once he’s gone, it magically turns into a tiger. So the tiger eludes him, just as Michael Jackson’s character eludes him – in fact, I feel in some ways that the tiger is Michael Jackson. Both are shape-shifters who use their supernatural ability to escape the detective, the police, the paparazzi … anyone who’s stalking them.

Nina: As I saw it, the “tiger” in Billie Jean seems to turn around and go back in the direction it came from – offscreen – while the tiles that light up continue moving forward. Nonetheless, it’s interesting to consider that the animal, like Michael, is a shape-shifter! Michael’s magic somehow rubbed off on him.

A word about the role of the paparazzi in “Michael’s” (and Michael Jackson’s) life. In Billie Jean, Michael is being photographed surreptitiously by the detective, which collapses the function of the paparazzi into that of law enforcement. I once read a sequence of articles about Michael Jackson that had been published in The Washington Post from 1982 to 1986. As early as 1984, and at the pinnacle of his success, I saw that there were already some signs that Michael Jackson would soon go from being the darling of the music world and a hero, to a figure of ridicule and derision.

This became the pattern for his life, as the Billie Jean film seems to oddly (and sadly) foretell. Even before the charges were first brought in 1993, the sentiment at large was that Michael’s celebrity – now linked to all things that are bizarre and over-the-top – had within it the seeds of criminality. That being the case, his only recourse would be to disappear: to remove himself from the prying gaze of the photographers and the public.

A photograph is itself “a lie [that] becomes the truth,” especially in its uses in the tabloid press, and elsewhere in the media. In Billie Jean, even when Michael shows up on the street leaning against a lamppost, the shot that comes out of that Polaroid Autofocus 660 camera in the store window reveals nothing of him, no sign that he had ever been there. “There was nothing left of the guy! Nothing at all!”

I continue to hope for more (and better) monitoring of those who represent the most powerful state in history, and whose actions make a mockery of the principles of American justice that have been loudly touted, and not carried out. The corruption that has existed within US political culture is something that traditional and present-day noir films could only hint at. Today, the police force is often equipped with dash cams or miniature recording devices. Hidden cameras in banks, retail stores, and streets are set up to monitor people, often without being detected, and certainly without permission. Yet at the same time, civilians are using iPhone and their own dashcam videos to ensure that the surveillors – who represent the state – can themselves be subject to surveillance, even by amateurs.

Willa: Yes, it’s like the panopticon is becoming a reality …

Nina: The panopticon (as conceived by 18th century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham) was to be a way that one guard could monitor inmates in a prison, and they wouldn’t know they were being monitored. According to Wikipedia:

Although it is physically impossible for the single watchman to observe all cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that all inmates must act as though they are watched at all times, effectively controlling their own behaviour constantly.

So, we are back to the idea of the voyeur again, as in Rear Window; only this time, the apartment dwellers across Jeffries’s courtyard know that they are being watched – they just don’t know when! But this model definitely adheres to the existing, one-way power structure, and not its reverse. The guard can watch the prisoners, but they cannot watch him. And if Michael Jackson was watched by “everyone,” who could he watch?

Again, Ralph Ellison’s protagonist in The Invisible Man, who narrates in the first-person (like the classic film noir detective, and like Michael Jackson’s character in Billie Jean), is able to describe the perceptions others have of him. In effect, by holding up a mirror to those who claim to “see” him, he reverses the customary social pattern, debunking the idea that human perception is a simple one-way dynamic. There is, he says,

a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality….

Many of Michael’s adherents are inclined to do battle – with the media, with the public, and with each other – to ensure that the “truth” of Michael Jackson comes out (as if there were any unsullied, pristine “truth” to be found). But my feeling is that we’d be better advised to look into our “inner eyes,” those eyes that are capable of looking both inward and outward. Michael Jackson’s quest for self-knowledge in this regard may parallel our own.

As Michael Jackson memorably sang, with lyrics by Siedah Garrett, “If you want to make the world a better place, take a look at yourself and make a change.”

Or to put it another way: in Rear Window, Stella, the insurance company nurse (played by Thelma Ritter) who takes care of the temporarily disabled L.B. Jeffries, remarks upon his habit of spying on his neighbors: “We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.”