Willa: One of the most intriguing features of Michael Jackson’s lyrics, I think, is the way he frequently shifts subject positions, looking at a story from one point of view, then another, and then another. This is something Joie and I have touched on a number of times – for example, in posts about “Morphine,” “Whatever Happens,” “Money,” “Threatened,” “Dirty Diana,” “Best of Joy,” “Monster,” and the Who Is It video – but we’ve never done a post that focuses specifically on his use of multiple voices. So I was very excited when Marie Plasse wrote this comment a few weeks ago:

I think that one of the most generally misunderstood or overlooked features of Michael’s art is the way he was able to occupy different characters in his lyrics and how … he expressed and explored aspects of his own psychic divisions and struggles. (It was perhaps a willful misunderstanding of this aspect of Michael’s art that precipitated, at least in part, the controversy over the lyrics of “They Don’t Care About Us.”)

This past fall I taught a full semester college-level course on Michael Jackson (“Reading the King of Pop as Cultural Text”) and one of the things the class found most surprising (but initially most difficult to do) was close-reading his lyrics and following the shifting perspectives. The complexities and the rapid shifts are really fascinating.

Marie is a professor of English at Merrimack College, and I’m very excited to talk with her about this aspect of Michael Jackson’s aesthetic that has intrigued me for so long. Thank you so much for joining me, Marie!

Marie: Thanks very much for inviting me, Willa. I’ve followed Dancing with the Elephant for a long time and have learned so much from your posts and the comments that readers send. I haven’t always had time to join in the comments as much as I would like, so I’m really happy to have this opportunity to talk with you.

Willa: Oh, so am I! And I’m so glad to finally have the chance to talk in depth about Michael Jackson’s use of multiple points of view. This is a recurring feature of his art, and a very important part of his aesthetic, I think – and personally, it’s something that has attracted me to his work for a long time. So I’m eager to find out more about how he uses it and how it functions.

Marie: I agree, Willa. Michael’s work as a lyricist is as complex as it is moving, and it’s so often overlooked as a key feature of his aesthetic. This might be because, as Joe Vogel points out in Man in the Music, Michael’s work as a songwriter is “much different from that of a traditional singer-songwriter like Bruce Springsteen or Bob Dylan” where the lyrics are much more “out front.” Joe goes on to suggest that Michael’s lyrics tend to get overlooked because they are only one of “several media to consider” amidst the music, short films, and dancing that are so prominently featured in his work.

But looking carefully at the lyrics on their own, and especially at their multiple points of view, reveals that Michael writes with great complexity and deep insight. I’ve gone back and reread all those posts you mentioned above in which you and Joie have talked about this quality of shifting perspectives and subject positions in Michael’s songwriting. I think you’ve already covered a lot of ground on this and opened up a lot of intriguing ideas about the possible meanings of the songs. So instead of offering my own close readings of certain lyrics, or at least before doing any of that, I thought I would try to think a bit further into this notion of multiple perspectives and voices to see where it might lead in a more general way.

Willa: OK, that sounds really interesting.

Marie: Reflecting on Michael’s use of multiple voices and shifting perspectives in his songs makes me think about his fervent interest in storytelling, which he talks about on the very first page of Moonwalk. His emphasis there is on how storytelling can move an audience and “take them anywhere emotionally” and on how it has the power to “move their souls and transform them.” He goes on to muse about “how the great writers must feel, knowing they have that power” and confesses that he has “always wanted to be able to do that.” He says he feels that he “could do it” and would like to develop his storytelling skills.

Just before this reflective section on storytelling ends and Michael swings into the beginnings of his own life story in the chapter, he mentions that songwriting uses the same skills as those of the great storytellers he admires, but in a much shorter format in which “the story is a sketch. It’s quicksilver.” Of course, we all know that by the time he wrote Moonwalk, Michael was already a masterful storyteller and his skills in this art only got better and better as time went on! He does “move [our] souls and transform them” very powerfully in his songs, short films, and performances, often using a multi-media approach that is much more complex than the traditional storytelling around the fire that he seems to admire so much as he opens the first chapter of Moonwalk.

Willa: That’s true. And I think you’ve raised a really important point in talking about how he conceptualized songwriting as storytelling. I was just reading Damien Shields’ book, Xscape Origins, and Cory Rooney talked to Damien about how important storytelling was in creating “Chicago”:

When working on the lyrics for the track, Rooney took inspiration from a conversation he’d recently had with one of Jackson’s collaborative partners – prolific songwriter Carole Bayer Sager – who urged him to write a song that tells a story. “[Michael] loves to tell a tale,” Bayer Sager told Rooney, so putting that advice into practice, Rooney went about writing a story for Jackson.

Rooney then passed that advice on to Rodney Jerkins, one of the authors of “Xscape”:

Rodney called me up and said, “Cory, we’re still confused. We don’t know what to write about. We don’t know what to do.” … So I told him, “Well, I got a little tip from Carole Bayer Sager. She told me that Michael is a storyteller. She said Michael loves to tell stories in his music. If you listen to ‘Billie Jean,’ it’s a story. If you listen to ‘Thriller,’ it’s a story. If you listen to ‘Beat It,’ it’s a story. He loves to tell a tale.”

So Carole Bayer Sager and Cory Rooney both confirm exactly what you’re saying, Marie – that Michael Jackson “loves to tell a tale.”

Marie: That’s a great connection, Willa. Thanks for reminding us about those passages in Damien’s book (which I thought was terrific, by the way. Thank you, Damien, for your wonderful work!). They really do underscore that Michael saw himself as a storyteller. And in order to have that power to move and transform an audience that he refers to in Moonwalk, a good storyteller definitely needs to be a master at crafting the point(s) of view from which the story is told, and to have the capacity to inhabit and express the experience of the story from those different perspectives (and the characters that they belong to).

Michael’s songwriting certainly displays his mastery of these essential aspects of good storytelling. As you’ve pointed out in so many different posts, he’s able to see his subject matter from many different perspectives and to shift in and out of those perspectives in interesting and meaningful ways. This is true across the full range of his work and, perhaps most interestingly, even within individual songs. He sees and he makes us see from all sorts of different angles and he occupies and places us in many different subject positions.

Willa: Yes, he really does. And often these subject positions and perspectives are ones that have rarely been considered before by mainstream culture. What I mean is, he frequently takes us inside the minds of outsiders – like the drug addict in “Morphine,” or the groupie in “Dirty Diana,” or the neighbor who has been labeled a “freak” and “weirdo” in Ghosts – and shows us the world from their perspective.

Marie: Absolutely, Willa. Clearly, the multiple subject positions and perspectives are in service of Michael’s larger mission of calling attention to the experiences of those who are “othered” or forgotten by mainstream society and who suffer for it. By shifting the perspective so often to these marginalized ones, he pushes us out of what may be our own relatively comfortable positions and makes us see through the eyes of the “other.”

And while we can easily agree that these features of Michael’s art are clearly those of a master storyteller, I would also venture to associate them with yet another literary tradition. Since I study and teach plays as part of my work as a literature professor, the multiple and shifting perspectives we’re talking about also make me think about what I would call Michael’s remarkably theatrical imagination. The way he tackles his subject matter through storytelling that imagines situations from different points of view and allows many different voices to speak reminds me of the special qualities of dramatic texts, where there is no single narrative voice, but rather the multiple voices of the various characters speaking directly to the reader or audience member in the theater.

Willa: Oh, that’s really interesting, Marie! It’s true that his songs often feel “theatrical” to me, and I think partly that’s because he tends to approach his songs visually, if that makes sense. For example, in Moonwalk he says,

The three videos that came out of Thriller – “Billie Jean,” “Beat It,” and “Thriller” – were all part of my original concept for the album. I was determined to present this music as visually as possible.

But I think you’re right – they also feel theatrical because they often sound like snippets of dialogue from a play, with interspersed lines spoken by different characters. I hadn’t thought about that before, but I think you’re really on to something.

Marie: What you say about his visual approach makes a lot of sense to me, Willa. I think that this visual approach to the songs in the short films is always what comes to mind first because the films have become so inextricably fused to the songs. And as we know, the songs lend themselves so well to the fully realized theatrical treatment that Michael gives them in the short films, where the different perspectives and characters in the song lyrics literally come alive in the embodied performances of the actors and the specific cinematic choices that structure the way the films are shot.

As we also know, Michael was meticulous in crafting the aesthetic and technical choices that governed his short films and live performances, working as a director rather than just the star. I remember seeing a number of comments from him on just how important camera angles – the very mechanism that creates perspective and point of view in film – were to him. I can’t recall specifically where I read this, but I seem to remember something that quoted him discussing the famous Motown 25 performance of “Billie Jean,” for example, where he explained that he designed exactly how his solo song should be presented through camera angles.

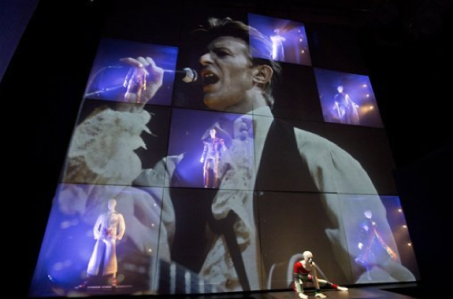

Willa: Yes, I remember reading that too. And you can actually see him controlling the camera angle in this video of the Jacksons’ induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. At about 14:45 minutes in, he pauses in his prepared comments and says, “I don’t like that angle. I like this one” and motions to the camera straight in front of him. Here’s that clip:

Marie: That’s a great example, too, Willa! He really was determined to control the perspectives from which the television audience saw not only his performances but also his public appearances at award ceremonies.

Willa: Yes, he was! We don’t normally think of something like this as a “performance,” but he did, and he was staging and directing it even as he was participating in it.

Marie: Exactly! That’s a great way to put it, Willa. And there’s also the endearing story of how he taught his son Prince about film by watching movies with the sound turned off so they could analyze each shot visually.

Willa: Yes, I was really struck by that story also.

Marie: So the visual connection you made, Willa, falls nicely into place as one of the many things we know about Michael and his work that indicate that he thought deeply about the issue of perspective and the significance of multiple and shifting points of view, whether those were conveyed through song lyrics alone, through the complex visualizations of his songs that he created in the short films, or even in public appearances like the one at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But it seems that in all this the song lyrics themselves have not been given the full discussion that they deserve.

Willa: No, they haven’t.

Marie: Their complexity, especially their multiple perspectives, really carries a lot of significance, and I do think that they work in similar fashion to dramatic texts. In order to understand the story that a play tells, we have to follow each character’s perspective and listen to each character’s voice carefully. Unlike in conventional narrative fiction, a play text isn’t dominated by a single narrator who controls our perspective and interprets events for us. It’s through the interaction of many different perspectives and voices unfolding over time that the play delivers its message and overall effect. And since it’s set up this way, there is a certain openness to a play that leaves a lot of room for individual interpretation.

Willa: And possibly misinterpretation, as you mentioned earlier about the uproar surrounding the lyrics to “They Don’t Care about Us.” Part of the confusion was that many critics didn’t seem to realize that when Michael Jackson sang “Jew me, sue me / Everybody do me / Kick me, kike me / Don’t you black or white me,” he was adopting the subject position of a Jewish person in the first three lines, and a black person in the fourth line. Both Jews and blacks have experienced the kind of slurs he’s addressing in these lines, and through these lines he’s showing solidarity with Jews – which is the exact opposite of the intolerance he was accused of. As Michael Jackson himself said in response to the scandal:

The idea that these lyrics could be deemed objectionable is extremely hurtful to me, and misleading. The song in fact is about the pain of prejudice and hate and is a way to draw attention to social and political problems. I am the voice of the accused and the attacked. I am the voice of everyone. I am the skinhead, I am the Jew, I am the black man, I am the white man. I am not the one who was attacking. It is about the injustices to young people and how the system can wrongfully accuse them. I am angry and outraged that I could be so misinterpreted.

So as you were saying, Marie, he adopts different personae at different moments in this song – just like the roles in a play. As he says, “I am the skinhead, I am the Jew, I am the black man, I am the white man.” Those are the different characters in this “play.”

So if we approach this song like a play, as I think you’re suggesting, Marie, and if we consider that the lines “Jew me, sue me” and “Kick me, kike me” are being spoken by character – a Jewish character who is protesting the prejudice against him – then the scandal makes no sense. It suddenly becomes very clear that Michael Jackson is denouncing anti-Semitism, not engaging in it – just as he said.

Marie: That’s a great example, Willa, and a really great way of explaining the danger of misinterpretation that opens up when multiple voices and perspectives are put out there with no overarching narrative voice to explain what’s going on. These lyrics, like play texts, require us to navigate among all the different perspectives we’re given and to make our own decisions about how we understand the subject matter. And this navigation can be pretty tricky in something as compressed as a song where, as Michael pointed out, “the story is a sketch. It’s quicksilver.” The controversy that erupted about “They Don’t Care About Us” clearly demonstrates the great risk for misinterpretation that comes along with the “multi-vocal” mode he used to sketch the story in this song.

But of course that controversy also underscored the disappointing and misguided lack of understanding among mainstream critics of Michael’s lyrical abilities, among their other problems. They just didn’t expect and weren’t receptive to the complexity that is clearly there. Armond White’s brilliant discussion of the HIStory album in Chapters 10 and 11 of his book, Keep Moving: The Michael Jackson Chronicles, addresses some of the larger issues at play in this controversy very well, connecting the critics’ misreading of the song’s lyrics to what he sees as white journalists’ habitual “denial of the complexity in Black artistry.” I think that White’s arguments about how the lyrics to “They Don’t Care About Us” work and about what drove that awful controversy are spot on.

Willa: I agree, though there may have been some corporate intrigue going on as well, as D.B. Anderson discusses in “Sony Hack Re-ignites Questions about Michael Jackson’s Banned Song.”

Marie: Yes, there’s probably a tangled web there, Willa, though from what I understand, critic Bernard Weinraub was not married to Amy Pascal, the Sony executive, until 1997, and his scathing New York Times review of “They Don’t Care About Us” appeared in 1995. Still, it appears that tensions between Michael and Sony existed even then, so it’s hard to know exactly what motivated that review.

But looking at it purely in relation to our discussion of lyrics, it seems clear that Weinraub didn’t read the so-called slurs in context and missed Michael’s intended purpose, which was to speak from the position of those being attacked. However, I also think that part of what makes those lyrics a lightning rod for the charges that Weinraub and others made is that since the words need to follow the staccato rhythm that drives the verses of the song, they are fairly elliptical, meaning that some key connecting ideas are left out in order to achieve that rhythm.

Willa: Oh, that’s an interesting point, Marie.

Marie: The lyrics in the verses of this song are really minimalist – they attempt to convey a complex set of observations and feelings in a really compressed way. In part, the compression is required by the medium: songs are short, so it wouldn’t work to go into long discourses.

But the shape of the verses and the way they spit out their words in a very truncated, staccato fashion is also part of the intended message and effect. The prejudice, hatred, oppression, and abuse that Michael rails against in the song do hit and bash, literally and metaphorically, and that’s what the pounding rhythm of these words conveys, along with Michael’s own disgust and frustration with these circumstances. The first verse sets the tone, offering a general picture of a world gone mad:

Skinhead

Dead head

Everybody

Gone bad

Situation

Aggravation

Everybody

Allegation

In the suite

On the news

Everybody

Dog food

Bang bang

Shot dead

Everybody’s

Gone mad

The second verse is a bit more challenging to understand, as the first-person narrator takes on the shifting subject positions that we’ve been talking about:

Beat me

Hate me

You can never

Break me

Will me

Thrill me

You can never

Kill me

Jew me

Sue me

Everybody

Do me

Kick me

Kike me

Don’t you

Black or white me

Clearly, Michael is alluding to his own recent tribulations here in lines like “Beat me / Hate me / You can never / Break me,” “Sue me,” and “Don’t you / Black or white me.” And “thrill me,” which at first seems out of place in this string of negative action verbs (“beat,” “hate,” “kill,” “kick,” etc.), also links the speaker here very directly with Michael Jackson, in an obvious allusion to “Thriller.”

Willa: Yes, I think so too.

Marie: But while we might first associate “thrill me” with “Thriller” or with something more generally positive, as in the colloquial usage “I’m thrilled to be talking with you here, Willa,” the word “thrilled” can also refer to excitement of a more negative or scary sort, like the fear we might feel at a horror movie. And read in the context of the “will me” which precedes it, “thrill me” might well be alluding to the terror Michael felt as the force (or “will”) of his accusers, the criminal justice system, and the media pressed in on him. So Michael is packing this one word with a lot of meaning: it’s a blatant, even defiant, allusion to his own phenomenal success with “Thriller” and to his reputation as a thrilling performer, but it also falls in line with the more negative actions that are stacked up in these lyrics. All together, though, Michael can be pretty easily understood to be saying something like, “Go ahead, do your worst, but you’ll never defeat me.” That’s clear.

But beginning with “Jew me” in line 9, the point of view shifts radically, as Michael starts speaking in the voice of a Jewish person who is the target of anti-Semitic slurs, making that person speak in that same “go ahead, do your worst” mode that he used in the earlier lyric. Here, the Jewish person seems to be saying, “Go ahead, call me those awful names, but you’ll never defeat me,” very much parallel to the mode of expression that was used in the lyrics a few lines earlier.

Willa: I agree.

Marie: But again, the actual expression here is elliptical and relies on the listener to recognize the parallel. And the lyrics don’t stick with this Jewish person’s point of view for long. Michael very quickly mixes in language that seemingly shifts the point of view back to his own personal situation, with “Sue me.” Then he switches back to the perspective of the Jewish person targeted by the anti-Semitic slur with “Kike me” and quickly follows that with a return to something that would be read as more directly related to himself, “Don’t you / Black or white me.”

If a listener is not following the shifting perspectives carefully, or if they are not even aware that this technique is being used, as seems to be the case with so many critics, then it would be pretty easy to decide that there is only one narrative point of view here and that the voice of the narrator is always Michael Jackson, speaking about his own personal situation and expressing his own point of view. As an English professor, I can’t help but be frustrated at the fact that the critics were making one of the most elementary mistakes you can make when reading literature, which is to confuse the speaker of the piece with the author.

Willa: Yes, it almost seems like a willful misreading of what he was saying.

Marie: Exactly. It’s not just that these critics are bad students of literature! There were many reasons for the media’s “misreading” of these lines. By the time this song was released in 1995, the general practice of attacking and ridiculing Michael was well established, fueled by complicated social and political energies that are now finally being carefully explored by many good scholars, journalists, and bloggers.

But if we look with attention at what is actually there in the words of the lyrics, we can see that by shifting the point of view so quickly, Michael is rapidly stepping in and out of different roles with the same kind of agility that he steps in and out of the choreographed group dances in his performances. He speaks for himself and about his own specific situation, and then he puts himself in someone else’s shoes and speaks their troubles, too. The effect of all this shifting is to erase the distinction between himself and others, to express solidarity and understanding in relation to those who are oppressed in different ways, and by doing so, to define really carefully the “us” that is the subject of the song and the focus of the chorus.

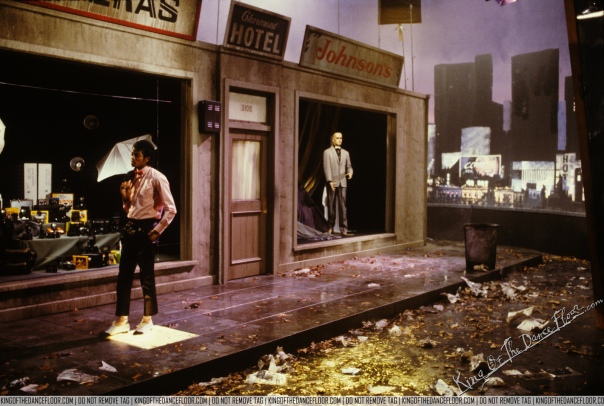

Willa: Yes, that’s a beautiful way of explaining this, Marie. And this ability “to erase the distinction between himself and others,” as you say, and “express solidarity … to those who are oppressed in different ways” is made very clear in the videos for the song, especially the original video – the one that’s become known as the “prison version.”

For example, in this screen capture, we see him in handcuffs with his hand positioned like a gun and his finger to his head, as if he’s about to be shot – and on the TV screen behind him, we see a prisoner of war in handcuffs who is about to be shot. In fact, this prisoner is shot as we watch, which is shocking and horrifying. And as this is happening, Michael Jackson sings “Bang, bang / Shot dead / Everybody gone bad.” So through the lyrics and these dual images, he makes a direct and visceral connection between himself and this anonymous prisoner.

By juxtaposing numerous images such as these, he links racial injustice in the US with war in Southeast Asia and hunger in Africa and political oppression in China and urban poverty in Brazil. In other words, he isn’t simply protesting the injustices he’s facing from a racially biased criminal justice system here in the US. He’s also linking that injustice with political, economic, and military oppression around the world.

Marie: Good point, Willa, and another terrific example. I think what you’re identifying when you say that the film makes clear that the perspective offered goes beyond Michael’s personal one reflects precisely the way a particular “production” of a play script works to clarify the words on the page by actually dramatizing the situation and embodying the different perspectives from which the characters speak. The particular creative choices that a production demands typically serve to specify and clarify those “open” or ambiguous elements that a written script presents.

So while the “They Don’t Care About Us” song lyrics alone might leave room for the kind of misinterpretation you mentioned earlier, the “prison version” makes it clear that the “me” who is speaking in the second verse of the song can be generalized to encompass all those who have been oppressed by hatred and violence, as in the example from the screen capture above. What we get in the film is a clearer and visually rich version of what the song lyrics tell us in much more elliptical terms, namely that Michael deliberately identifies with these many different oppressed individuals as part of an “us,” rather than as a more distant “them.” To me, this is emblematic of the often misunderstood beauty and power of the HIStory album as a whole. Michael’s personal anger and frustration extend beyond the personal to encompass much more than that.

Willa: I agree, and that’s part of what makes him such a powerful artist, I think.

Marie: Yes, absolutely. But in the lyrics to individual songs like “They Don’t Care About Us,” all this unfolds very fast (as Michael said, songs are “quicksilver”), and without clear markers to clarify who is speaking, as one would find in an actual play text where the speeches are preceded by the speaking characters’ names. The complexity of what Michael is doing here is easy to miss if you’re not paying attention or if, as I think many of the critics were, you’re responding with a pre-ordained agenda in place.

Willa: Exactly.

Marie: But to move on a bit from “They Don’t Care About Us” and take this playwriting angle I’ve suggested a step further, we might say that one way to think about the multiple perspectives and voices Michael creates in his songs is to note that they are often used to set up explorations that are structured as powerful conflicts (between individuals or ideas). Conflict is a key element of the storytelling that goes on in plays (and many other forms of literature as well), and it’s one of the basic ways that these texts keep us interested. We get invested in the struggle, we want to see what the terms of it are, we might identify with a certain character within it, and we want to see what happens in the end.

Willa: Oh, absolutely – either conflicts in personal relationships, like we see in “Billie Jean” or “In the Closet” or “Whatever Happens,” or between groups of people, as in “Beat It” or “Bad.” Or an individual fighting authority, as in “Ghosts” or “This Time Around.” Or internal conflicts, as in “Will You Be There” or “Stranger in Moscow.” Or large cultural conflicts as in “Earth Song” or “Black or White” or “HIStory” or “Be Not Always” or even “Little Susie.” That’s a really important point, Marie. A lot of his songs are driven by powerful conflicts, as you say – though often in complex ways where the protagonist sympathizes with the antagonist to some degree, so it’s rarely a simple “us” versus “them” situation.

Marie: That’s a really good survey of the different kinds of conflicts Michael lays out in his songs, Willa, and I love how you can pull those titles together so quickly! It’s so much fun to talk with you about this topic! And yes, I agree that while many songs start off with clearly drawn conflicts, they end up complicating those basic oppositions, but we can see very clearly even in songs that remain starkly polarized how he evokes both sides really powerfully and is able to deftly sketch out what’s at stake in the conflict by invoking the shifting subject positions we’ve been talking about.

Willa: Yes, it’s really remarkable.

Marie: In “Scream,” for example, where it’s clear in the first part of the first verse that he’s expressing his opposition to the abuse he suffered from the press and the culture at large after the 1993 allegations (“Tired of injustice, tired of the schemes . . . as jacked as it sounds, the whole system sucks”), he follows up in the second part of the first verse with a more detailed invocation of the conflict, using the “you” pronoun in opposition to “me,” “mine,” and “I”:

You tell me I’m wrong

Then you better prove you’re right

You’re sellin’ out souls but

I care about mine

I’ve got to get stronger

And I won’t give up the fight

The rapid oscillation of the pronouns here makes me think about how spectators’ eyes move back and forth as they watch a tennis match between opposing players. The back and forth between the perspectives of the “I” and the “you” reads at first like a verbal argument (“You tell me I’m wrong / Then you better prove you’re right”), but the same opposing pronoun structure is used to ramp up the stakes of the conflict really quickly in the next couple of lines: “You’re sellin’ out souls but / I care about mine.” Now the apparent argument about who’s right or wrong takes on much larger proportions, with the “you” attached to the evil-sounding act of “sellin’ out souls” (which works both metaphorically as a way of describing terrible betrayal in economic/religious terms, and more literally in connection with the greed that was involved in the efforts to destroy Michael) and the “I” declaring how important his soul is to him and vowing to get stronger so as to keep up “the fight.” In just a few lines, the really high-stakes conflict has been sketched out for us.

Willa: It really has. And it’s made all the more intense because of the very real conflicts he was facing, conflicts that can lead us to fill in the “you” position in different ways – as referring to the media, the police, the judicial system more generally, the music industry, the insurance industry, the specific accusers, the general public, and so on. The ambiguity of that unspecified “you” lets us fill in that slot with a multitude of characters who were complicit in “selling out souls.”

Marie: That’s a great insight, Willa. I think you’re right about how that “unspecified you” works as an open slot that can be filled in with a number of different characters. And in typical Michael fashion, things get even more complicated in the chorus, where the second person “you” references shift really quickly as the lines move forward:

With such confusions

Don’t it make you wanna scream?

(Make you wanna scream)

Your bash abusin’

Victimize within the scheme

You try to cope with every lie they scrutinize

Somebody please have mercy

‘Cause I just can’t take it

Here, as in other songs, the “you” is ambiguous, and expansively so.

Willa: Yes, and I like the way you put that, Marie. It’s an “expansive” you that can stretch to encompass all of us listening to his words.

Marie: Yes, it addresses us directly and urges us to join in and identify with the speaker in his indignant question (“don’t it make you wanna scream?”) but it also sounds like he is addressing himself, as if he is suddenly on the outside looking in and asking himself about what the circumstances make him feel, just to double check on the accuracy of his feelings, or perhaps to give himself temporary relief from occupying the besieged position of “I” in this scenario. And the call and response from the background vocal that repeats “make you wanna scream” suggests yet another perspective, from a chorus that is echoing this idea, as if to confirm that yes, all this does make you wanna scream.

In the next two lines, the perspective referenced by the second-person pronoun “your” seems to shift dramatically, to those victimizers who are perpetrating all the things that make “you” and the speaker himself want to scream: “Your bash abusin’ / Victimize within the scheme.” Then in the following line, we’re back into the perspective of the previous “you” who is reacting to all this: “You try to cope with every lie they scrutinize.”

And finally, the last two lines of the chorus land squarely in the first-person, pleading, “Somebody please have mercy / ’Cause I just can’t take it,” and the rest of the chorus expands this plea into a more aggressive demand to “Stop pressurin’ me,” with the first-person objective pronoun “me” repeated eight times, once in every line, so that it’s painfully clear who is experiencing all the pressure! The effect of all this for me – the shifting perspectives described by the quick pronoun shifts – is that I feel like my head is being spun around! Trying to follow the perspectives creates for me a version of the “confusion” that the speaker is describing and makes me able to imagine just a tiny bit of what it must have felt like to be in the whirlwind of abuse that Michael went through.

Willa: That’s a great description, Marie! And maybe this “confusion” also works to complicate the distinction between the heroes and the villains. Because there are so many shifts in perspective, the “you” is accused of “bash abusin’ / Victimize within the scheme” but is also asked, “Don’t it make you wanna scream?” as you say. So maybe the villains are pressured by the system too? Maybe it makes them want to scream also? And maybe we need to look at our own complicity in the system and change our own ways also?

Marie: I like that reading very much, Willa! It goes along with the idea from the first verse where Michael says, “The whole system sucks.” So it would make sense that the villains are caught up in it in ways that are harmful to them as well, whether they admit it or not. Your point about our own complicity in the system is interesting, too. We know from songs like “Tabloid Junkie” that Michael doesn’t let us off the hook either, as he reminds us of the role we might play in the system, specifically through the consumption of tabloids: “And you don’t have to read it / And you don’t have to eat it / To buy it is to feed it . . . And you don’t go and buy it / And they won’t glorify it / To read it sanctifies it.”

Willa: Exactly. That’s a great connection, Marie.

Marie: It’s also really interesting, too, that since “Scream” was recorded as a duet with Janet, the speaker who utters “I” literally shifts as each of them sings their assigned part. Janet’s sharing the lead vocal with Michael is a solid act of support for her brother (even before she appeared with him in the short film). When she sings as “I,” she’s singing from his perspective in all the “confusion” and also joining in his opposition to it.

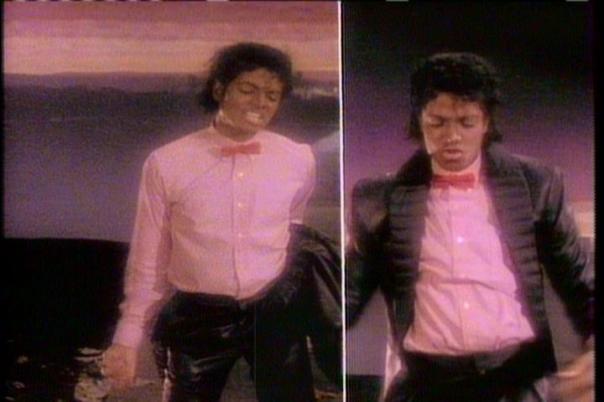

Willa: Oh, that’s interesting, and a really important point, Marie. I hadn’t thought about that before, but you’re right. And again, the ideas expressed in the lyrics are reinforced by the video, where Janet and Michael Jackson are repeatedly pictured as almost mirror images of one another, identically dressed and reflecting each other’s feelings and facial expressions. Here are some screen captures:

So unlike a play, where one actor would typically play one character while the other plays a different character – for example, where one might play the victim while the other takes on the role of victimizer – in Scream it’s like they take turns playing the same character. That’s really interesting, Marie.

Marie: Exactly, Willa. And as they take turns playing the same character, I think that what we see, particularly in Janet’s willingness and ability to take on the role of the victim in “Scream,” is a clearer, more easily understood version of what Michael does on his own in so many songs where he himself takes turns playing all the characters, as in “They Don’t Care About Us.” In Janet’s case, it’s clear that she empathizes with her brother and can understand deeply what he’s going through. She shares and can give voice to his anger and frustration, not only because she’s his sister and she loves him, but because as a famous artist she’s also in the public eye and knows what it’s like to be subject to the abuses of “the system.” (And just think, “Scream” was recorded long before the infamous 2004 Superbowl “wardrobe malfunction” that blew up into such a nightmare for Janet.)

Thinking about Janet’s role in “Scream” also reminds me of that great moment at the 1995 MTV Video Music Awards when the Scream short film won the award for Best Dance Video. When she went up to accept the award with Michael, Janet appeared in a cropped t-shirt that said “Pervert 2” on the back!

Willa: I was just thinking about that! As you were describing so well how she shoulders some of his burden in “Scream” by stepping into his subject position and speaking from his perspective – “giv[ing] voice to his anger and frustration,” as you said – I suddenly flashed on her in the “Pervert 2” t-shirt. That really was a powerful act of solidarity.

Marie: I love how, by choosing to wear this shirt at such a widely viewed event, Janet performs a really cheeky extension of her identification with Michael in the song and the film, as if to say, “Well, if my brother is a pervert, then so am I!” Here’s a link to the awards telecast. Janet appears in the shirt right around 1:15.

The larger point here, though, is that Michael’s skill at incorporating different subject positions and points of view in his song lyrics allows him to convey so many complex and important messages in the space of the “quicksilver sketch” that the song medium requires. As Janet did with Michael in “Scream,” Michael is able to forge strong connections to the “others” that he invokes through the shifting points of view in many different songs. It’s not always about this same level of empathy that Janet displays in “Scream,” but it does suggest how important it is for him to present many different perspectives and voices. And it’s significant that he chooses not to just describe them in the third person (“he did this” or “she feels that”) but to speak “as if” he himself were these other individuals, as he does in “They Don’t Care About Us.”

Willa: I agree, and in doing so he immerses us as listeners in those subject positions as well – not only in “Scream” and “They Don’t Care about Us” but in many other songs also.

Marie: To me that demonstrates a remarkable spirit of openness, generosity, community, and heartfelt interest in people and situations beyond himself – all those qualities that we recognize and admire in Michael.

Willa: Yes, absolutely, and a lifelong habit of empathy that led him to reach out emotionally and try to consider a situation from many different perspectives, even perspectives in opposition to his own.

Marie: And just like Shakespeare and his contemporaries who worked so masterfully within the confines of the conventional fourteen-line, rhymed sonnet form, what he does is remarkable to me precisely because he’s working in such a compressed form with so many of its own constraints – song lyrics can’t be too long, they need to work with the musical rhythms and pitches of the song, they need to be pronounceable for the singer, in most cases they need to rhyme, etc.

And while it may sound crazy, I mean to draw the Shakespeare analogy here very deliberately. I specialize in Shakespeare, so he’s always on my mind and I can’t help but make the connection. But more importantly, I think that Michael’s lyrics are overlooked or misunderstood (as they were with “They Don’t Care About Us”) in part because people in general, and especially certain critics, are often reluctant to think of pop song lyrics as complex forms of language that spring from poetic impulses that are not that different from Shakespeare’s or those of any other venerated poet.

Willa: I agree completely – though coming from you, as a Shakespeare scholar, that means a lot!

Marie: As we’ve said, going back to the commentary I mentioned earlier from Joe Vogel, with Michael’s work there are so many other “channels” of expression to pay attention to – the music, the dance, the films, the live concerts – in short, the full spectacle that comprises the incredibly compelling pop phenomenon known as “Michael Jackson” – that the complexity of the lyrics alone is often overlooked. (And this is even putting aside the additional effects of all the controversies and tabloid distortions that played into how Michael was viewed from the mid-1980s onward.) But I also think that there’s a certain elitism that comes into play that’s connected to the divide that still persists in some people’s minds between so-called “high culture” and “low culture” or “pop culture.”

Willa: Absolutely, and it’s really curious how that line is drawn. Of course, for some critics no pop music is high culture. But even for those who concede some ground to popular music, the distinction often feels arbitrary. For example, for some reason U2 is generally regarded as high brow and the Beach Boys are not, even though the Beach Boys were much more experimental musically, incorporating complex arrangements and harmonies and pioneering new recording techniques that changed the course of music history.

That’s just an example, but my point is that the division between “high” and “low” art often doesn’t make much sense, and seems to depend more on some academic “cool” factor rather than artistic merit.

Marie: The Beach Boys example is a great one, Willa. I recently saw Love and Mercy, the new film about Brian Wilson, and learned so much from it about how complex and innovative Wilson’s music was. A lot of recent academic work has critiqued that “high/low culture” divide and there are many music and cultural critics who don’t let it stop them from taking the work of popular artists seriously. (Serious considerations of hip-hop, for example, have been under way for a long time now, as evidenced not only in the music press, but in academia, where we see specialized journals, books, courses, and even college-level majors and minors in hip-hop studies.)

But as we know, Willa, as an artist whose popularity was (and still is) unprecedented around the world, Michael was often mistakenly pigeon-holed as just an “entertainer” focused mainly on mainstream commercial success as shown in record and ticket sales, rather than being viewed as a serious artist whose keen intelligence, sharp social insight, and nuanced emotional understanding got expressed in the language of his lyrics as well as in all the other media he used.

Willa: Absolutely. You expressed my feelings exactly, Marie, though much more elegantly than I could. And it continues to mystify me how critics could have overlooked and undervalued his work for so long.

Marie: It is hard to fathom, for sure. But working on this post has made me see even more clearly that there really have been a bunch of different obstacles preventing the kind of careful consideration and appreciation of Michael’s lyrics that we’re trying to do here. And I think we’ve only begun to scratch the surface of what there is to say about how Michael’s lyrics use shifting subject positions, Willa!

Willa: I agree, and thank you so much for joining me, Marie, to try to gain a better understand of all this. You’ve given me a lot to think about, and I really appreciate your insights into the “quicksilver” quality of his songwriting – of his ability to not only tell a story but sketch out a miniature drama in his songs. I’m really intrigued by that, and want to ponder that some more. Thank you for sharing your ideas!

Marie: It’s been a pleasure, Willa. Thanks again for coming up with this topic and inviting me to think about it with you!